William Hogarth (1697 - 1764)

Painter and engraver William Hogarth was born in London. He abandoned formal education in 1713, and became an apprentice engraver, turning out designs for silver plate. Determined to become a painter of historical scenes, Hogarth was forced to adapt to the need to support himself and his family upon the death of his father and so became a tradesman-engraver, producing shop cards and book illustrations, in addition to designs for silver plate.

While training as a painter at the St. Martin’s Lane Academy, Hogarth produced his first print. At the time, artists sold their graphic work through print dealers and booksellers and were frequently victimized by the extortionate sales commissions imposed by them. Resolving to deal directly with the buying public, Hogarth enjoyed his first great success in 1732 with the publication of the six engravings that constituted The Harlot’s Progress, which are based on a suite of paintings produced by Hogarth on the same subject that were destroyed in a 1755 fire. The prints, sold by subscription, portrayed the downfall of a simple country girl swept into a life of prostitution and condemned to an early death from syphilis.

The great success of The Harlot’s Progress brought Hogarth widespread fame and influence, together with numerous imitators who copied his work. Hogarth’s determination is held to be principally responsible for the enactment of the Copyright Act in 1735, the first law of its kind protecting an artist’s work from predatory imitators. The Rake’s Progress of 1735 and Marriage à la Mode of 1745 followed. These moralistic suites were followed by others in their turn, underscoring the artist’s sincere moral and humanitarian concerns. Taken as a whole, they gave Hogarth well-deserved recognition throughout Europe and North America. In 1757 he was appointed Sergeant Painter to the King. William Hogarth died at Leicester Fields, London.

A Harlot's Progress

Suite of six engravings; overall sheet sizes are approximately 15¼" wide and 12¼" long. All sheets have narrow margins of approximately 1/4" outside of the plate mark. The Harlot's Progress was originally published in 1832. The engravings offered here are second state prints issued ca. 1742 - 1744 and identified as catalog numbers 121 - 126 in the Ronald Paulson catalog raisonné Hogarth's Graphic Works, published by Yale University Press in 1965. Second state prints of A Harlot's Progress are chiefly identified by the addition of a cross in the bottom margin as well as by one or more modifications made by Hogarth to the original engravings. The images are uniformly clean and bright, with only minor flaws in the sheets. Please call for more detail.

$1,500

M(oll?) Hackabout stands in the yard of the Bell Inn in Cheapside, having come to London seeking employment as a seamstress, suggested by the pincushion and scissors hanging from her waist. She stands, innocent and modestly attired, in front of Elizabeth "Mother" Needham, the notorious procuress who operated a brothel in Park Place, and who is examining the country maid's youth and beauty. Her face is adorned with several "beauty patches", used primarily to conceal the ravages of syphilis. Not long before the publication of A Harlot's Progress, Mother Needham was stoned to death by the crowd gathered at the pillory not far from her bordello where she was placed on public display. Behind the two women stand Colonel Francis Charteris, a wealthy and influential man and a notorious satyr who preyed upon unsophisticated young arrivals to London and lured them into his household employ. The man behind Charteris is one or another of the pimps whom he kept at hand to assist in disposing of his most recent conquest. On the left, the old clergyman, whose horse has knocked over a stack of pots, is totally absorbed in the letter that he is holding, utterly unaware and unconcerned with the unsavory scene playing out behind his back.

A Harlot's Progress, Plate 2

Whether she had fallen prey to Colonel Charteris or to Mother Needham, Moll Hackabout is now the kept mistress of a wealthy London Jew and lives in a well-appointed town house. His unexpected arrival while his mistress and her aristocratic young lover have been dallying in bed prompts Moll to drastic action. She kicks a table over to create a diversion that enables the younger man to make good his escape. Her keeper's astonishment in the face of such impertinence, mirrored by the expression of the startled monkey at his feet, suggests that her days under his roof may be numbered.

Part of a complete set of six engravings. See above.

A Harlot's Progress, Plate 3

Having betrayed her keeper, Moll has lost her comfortable berth and is now a common prostitute, living in proximity to her fellow streetwalkers somewhere near Covent Garden as the tankard on the floor suggests. Moll casts a coquettish glance towards the viewer, unaware that Sir John Gonson, a magistrate widely known as the scourge of prostitutes, passed through her doorway leading bailiffs to arrest her. The two medicine bottles on the small table to the right of the scene suggest that the small black spots on her face portend an even worse fate than her impending imprisonment, and that syphilis has Moll in its inexorable grip.

Part of a complete set of six engravings. See above.

A Harlot's Progress, Plate 4

Moll is now beating hemp in Bridewell Prison, the Westminster lockup for prostitutes, card sharps and other petty criminals. Her precipitous fall is emphasized by the contrast between her still elegant clothing in the setting of this dreary and austere place. Her bewildered, weary expression amuses some of her fellow inmates - one mockingly touches the lace and silk of Moll's finery as she directs a wink and a knowing grin at the viewer. The warder reminds Moll that the log and chain await her if her if she flags in her duties. Behind her are the stocks, presently occupied by another, but a constant reminder of their availability to her as well.

Part of a complete set of six engravings. See above.

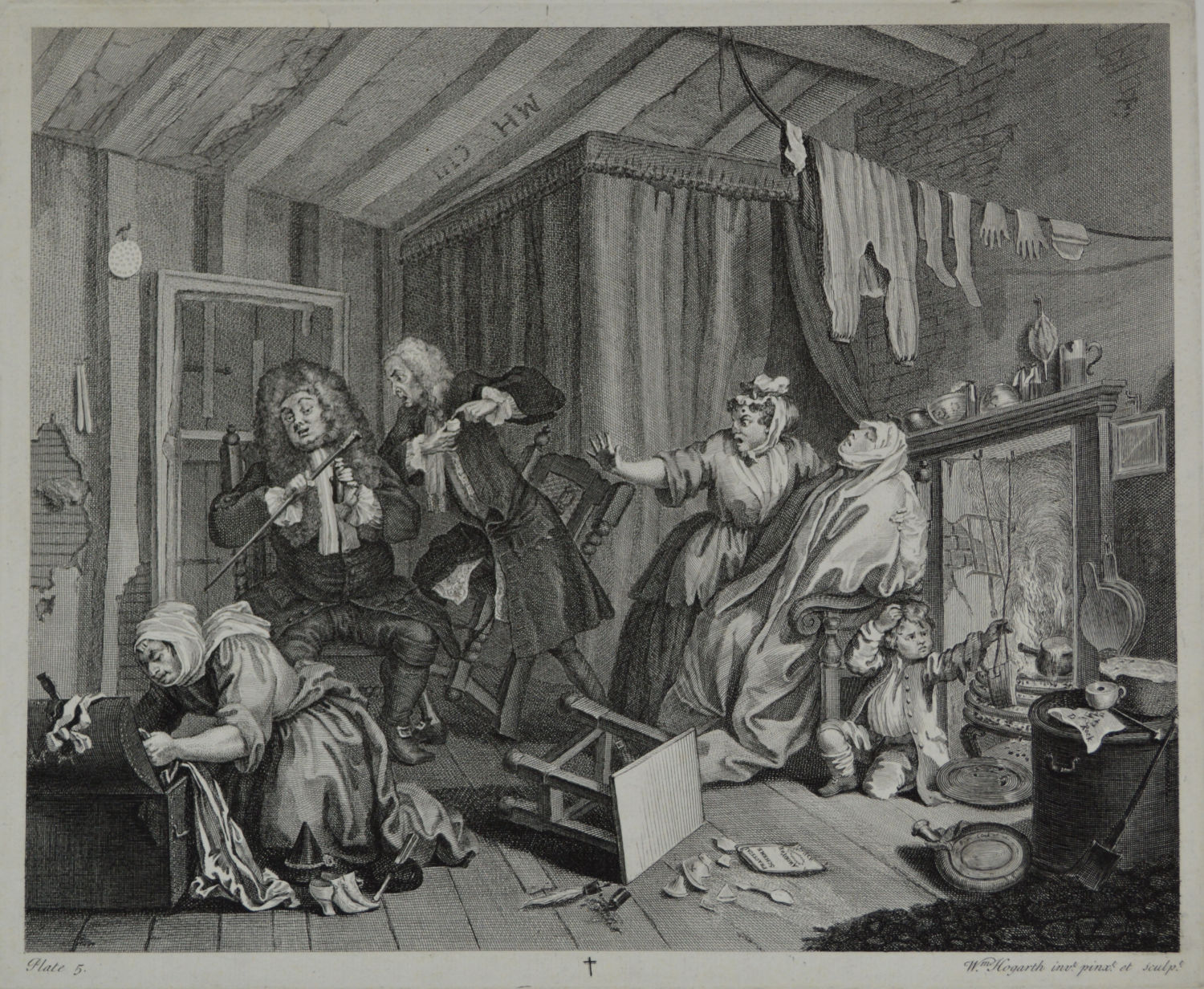

A Harlot's Progress, Plate 5

Now returned to her garret, Moll is dying from syphilis. The "sweating blankets" envelop her body as the servant who tends Moll turns angrily on two "doctors" - the fat Dr. Richard Rock and the thin Dr. Jean Misaubin - as they debate the merits of their respective quack cures, indifferent to the evident distress of their patient. Moll’s illegitimate son sits to her left at the hearth. Her teeth lie scattered on the paper, loosened by the mercury that was a commonplace "cure" for the disease. The woman on the left of the scene is rummaging through Moll's trunk of clothes in search of a suitable dress for her burial.

Part of a complete set of six engravings. See above

A Harlot's Progress, Plate 6

This final funeral plate presents "mourners" - most of them fellow prostitutes - gathered around Moll's coffin in anything but a mournful state. Two of the women use the gathering as an opportunity to ply their trade: On the left a parson, staring into space, finds his way beneath the skirt of the young and as yet unblemished bawd at his side, who looks toward the viewer with half-closed eyes and a faint smile as the clergyman distractedly spills his brandy. The undertaker, at the right of the scene, has similar designs upon the street-worn and syphilitic woman to his left. Moll's son, the chief mourner, sits on a box near the head of the coffin, seemingly unaware of anything but the top that he is winding. Sprigs of Yew and of rosemary were commonplace at funerals of the era because they were thought to be a preventative against infection.

Part of a complete set of six engravings. See above